Imagining a new system for land use and zoning

There is a famous saying that systems do exactly what they are designed to do. The housing system is no exception. It does what it was built to do – preference some populations at the expense of others and keep safe, stable housing out of reach for too many of our neighbors.

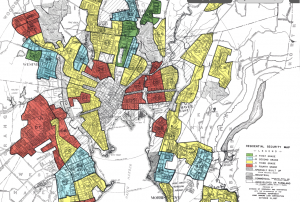

Targeted, systematic, and racialized policies and practices were designed to exclude Black people and other minorities from homeownership, decent affordable housing and thriving neighborhoods. For example, in the 1930s, the Federal Housing Administration through a practice known as redlining, labeled areas in and near African-American neighborhoods as hazardous and refused to insure mortgages in these communities. While redlining is now illegal, predatory loans, subprime lending, gentrification and displacement continue to shape who is able to own a home or afford quality housing in flourishing communities.

As a result, there are significant racial disparities in who becomes homeless, pays more than 30% of their income on rent, lives far away from good jobs and schools, and gets evicted. Even before the pandemic Black Americans made up 13% of the U.S. population but accounted for 40% of all people living without a home, and landlords filed evictions against Black renters at nearly double the rate of white renters.

It is time we imagine a new system.

Policies got us into this mess and policy can get us out of it – if and only if we are as targeted and inventive in our efforts to undo the harm caused by the current system.

That requires us to focus on the root causes of these disparities, and the people most impacted. Simply put, we will never end homelessness if we do not focus on Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) with extremely low incomes and address some of the root causes of homelessness, including racist housing, zoning and land use policies that perpetuate housing instability.

The Melville Trust is committed to advancing new approaches to ending homelessness in America, stepping beyond our comfort zone to innovate and elevate ideas that will help break through existing barriers in our housing system. To that end, as part of our new strategy and focus on BIPOC with extremely low incomes we are hosting small imagination sessions to inform our work. Last month we invited community organizers, housing justice advocates, researchers, urban planners, and others to an “imagination session” around zoning, housing and land use. Our goal was to yield new ideas; solutions that look at existing strategies in fresh ways; or promising approaches that need scaling.

Our friends/colleagues wrestled with the following questions:

- How do historical and present-day housing, zoning and land use policies impact the ability of BIPOC with extremely low incomes to have safe, affordable homes that allow them to thrive?

- What policies are needed to advance an anti-racist land use agenda that will help preserve and produce more affordable housing without exacerbating gentrification or displacement?

- What would it take to change the narrative around who deserves housing and where?

- What would it take to democratize development decisions and design housing and places where BIPOC matter and thrive?

- What would it take to ensure that race is no longer a predictor of housing and health outcomes?

Here are some of our insights from this first conversation:

- New reforms cannot be based on old ideas. For land use, zoning and housing policy to produce equitable outcomes underlying challenges must be exposed, interrogated and, in most cases, deconstructed or transformed. Without this step new policies and reforms will continue to disconnect and disempower BIPOC individuals and communities. For example, community mapping projects highlight how land use policies have contributed to persistent racial segregation and racial disparities. The Alliance for Housing Justice also has a great resource on the 27 Ways Racism and White Supremacy Impact Housing.

- Build and shift power. Philanthropy can play a critical role in funding the organizing and operational infrastructure needed to protect existing housing victories and advance new ones. Some emerging opportunities include investing in community land ownership models, supporting the expansion of tenant unions and building bridges between rural and urban unions to create multi-regional, multiracial tenant organizations with statewide power.

- Move from restrictions to restoration. Zoning is by nature meant to restrict and separate us. To build more equitable communities, we must shift our mindset from restrictions to building bridges and community connections and even reparations.

- Identify and eradicate barriers. State and local governments need to analyze suggested policies through an equitable lens to identify and correct for any unintended negative consequences. Several participants talked about the need for zoning audits to identify barriers to and opportunities for anti-racist policy change.

Over the next few months, we will be facilitating additional imagination sessions and exploring how the Trust can shift its grantmaking to achieve our vision. We are truly grateful to our colleagues for sharing their wisdom and helping us deepen our understanding of the work ahead. We look forward to sharing our learning journey with you.